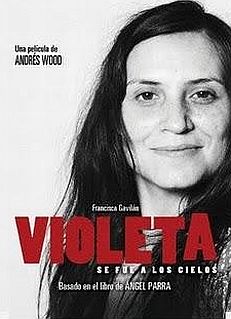

The intense, remarkable life of the Chilean singer-songwriter Violeta Parra is explored with sensitivity and exquisite lightness of touch in Andres Wood’s “Violeta Went to Heaven.”

The intense, remarkable life of the Chilean singer-songwriter Violeta Parra is explored with sensitivity and exquisite lightness of touch in Andres Wood’s “Violeta Went to Heaven.” Featuring a searching central perf from Francisca Gavilan, this beautifully lensed portrait moves elegantly back and forth in time to limn the life of a woman who perpetually struggled to find her place. Chile’s Oscar submission reps a formidable addition to Wood’s already solid oeuvre, and even its specifically Chilean subject is unlikely to prevent it from following Wood’s “Machuca” into offshore arthouses.

Although some poetic license is inevitably taken, the pic is closely based on the events of Parra’s own life, structured around a TV interview the singer gave in 1962.

Raised in poverty in southern Chile as the daughter of an alcoholic schoolteacher named Nicanor (Christian Quevedo), Parra was a spirited child right from the start. As an adult, she was deeply romantic and deeply political, writing songs that could be achingly lyrical or stridently defend the oppressed. Key events shown include Parra’s travels through the Andes mountains giving shows as a duet with her sister Hilda; her visit to an old man in the countryside from whom she wants to learn songs, but who refuses to sing following the death of his grandchild; her trip to the Intl. Youth Festival in Poland, from which she returns to find her year-old daughter has died of pneumonia; her time in Paris, where she exhibits her work at the Louvre; her tempestuous, on-off relationship with anthropologist Gilbert Favre (Thomas Durand); and her installment of an arts center in a remote tent back in the Andes.

These events are shown radically out of sequence, though Andrea Chignoli’s precision editing ensures that scenes set years apart are rendered illuminating rather than confusing by their juxtaposition. Some welcome comic relief comes during the 1962 interview, in which Parra deals patiently with the snide questions of a right-wing Argentinean interviewer (Luis Machin).

Gavilan delivers a profoundly committed, rangy perf that manages to be intense, gutsy and nuanced all at once, and bespeaks an awareness of the importance of getting Parra right for the sake of Chilean auds. The script allows for a warts-and-all portrait that’s far from simple hagiography. Parra’s multiple contradictions are all there: She’s headstrong but insecure, sociable but lonely, adventurous but home-loving, and crucially, never quite able to be a good mother to her children. (Pic is based on the memoirs of one of them, Angel.)

Typically of Wood’s films, production values are topnotch. The use of locations is especially strong, and lenser Miguel Joan Littin, Wood’s longtime collaborator, renders the peculiar light and textures of an Andean mountain village as capably as he does those of the banks of the Seine by night. Visually, the pic is never dull and at times demonstrates a daring sense of framing, as with a lovemaking scene shot through the gaps between floorboards.

Pic features about 20 mostly guitar-based songs that rep a good selection of Parra’s work, although her most popular tune, “Gracias a la vida,” is missing. The highlight is a searing, soul-baring performance of “El gavilan” (The Sparrowhawk), which features the line on which the pic might have been built: “I have nowhere to be.”